Before 1831, cemeteries were treated as public parks that people went to for picnics, to relax, go on dates and watch carriage racing.

Yes, the first public parks were cemeteries.

But the creation of MODERN cemeteries that separated the living from the dead changed the West’s relationship with death, grief and preserving memory.

“Entrance gates [to cemeteries] marked where one world ended and another began.” - Kaley Overstreet

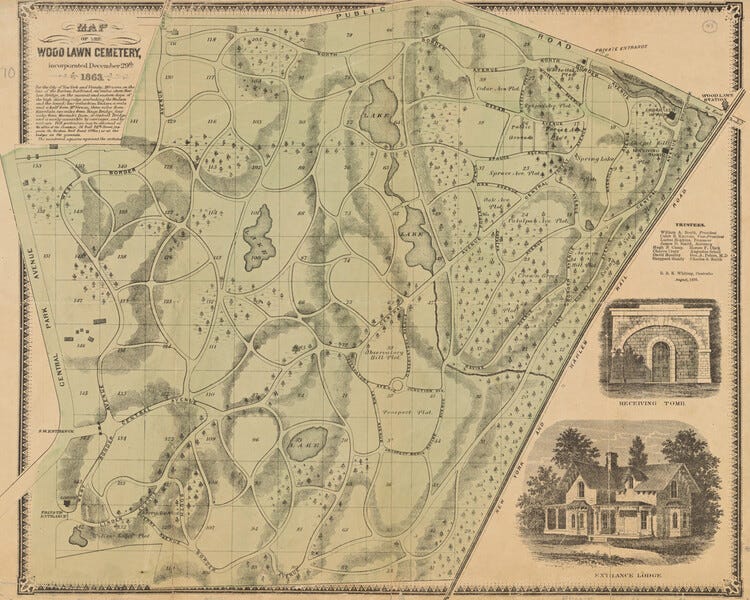

Cemeteries were once open, lively, beautiful spaces with sculptures and gardens, doubling as centers for community and art. They were so popular that maps and guidebooks were issued to visitors.

These cemeteries differed from old burial grounds at churches which were unsanitary, expensive, crowded, and dangerous.

Up to 7 coffins were stacked on top of one another. When it flooded, some coffins would break open and spill the decaying bodies onto the street. This only made the cemeteries that were designed like modern day parks even more popular.

With that said:

Death used to be social, public, familiar.

In the 1800s,

“death was more frequent as waves of diseases swept the world and people had shorter life expectancies… it was viewed more as a deep sleep.” - Kaley Overstreet

People would die at home. Their bodies were washed by loved ones and laid out in the living room for people to come talk to. Families would sleep in the same room as them. Grieving was shared and slow.

The Birth of a Death-Denying Culture

Now, death is hidden, isolated, professional.

Once cities built dedicated parks and cemeteries, the dead and the living were separated not only physically, but culturally.

Most people now die in hospitals, alone. Their bodies are handled by strangers. Grieving became quick and quiet.

Thus, a culture and system was built on the denial of death.

Cemeteries rebranded as “creepy.”

Death became taboo.

Cemeteries were removed from cities to prioritize private spaces like real estate so people no longer had regular reminders of mortality.

“Cemeteries operate as alternate cities—cities of the dead.” - Rebecca Greenfield

People then began fearing death and replaced respect for the dead with horror.

“Look at themes in popular culture, at how often the worlds of the living and dead intersect and how disastrous that often is. Think of zombie movies—havoc usually ensues.” - Rebecca Greenfield

What happens to the psyche when death is out of sight?

We become:

afraid of aging and addicted to youth.

inconvenienced by grieving.

dependent on medicine and miracles.

We have become “increasingly uncomfortable with mortality” as described by historian, Philippe Ariès.

We prioritize outrunning death and extending life, and it’s evident in industries such as beauty, fitness, food, wellness, pharmaceuticals, and finance.

But life itself is not enough. It is deeply rooted in Western culture to justify our existence and worth by our output.

We prove this by:

looking young to stay competitive.

discriminating against older workers.

isolating and hiding our elders in retirement homes.

Because…

We fear economic death more than the afterlife.

The Western dream of living forever is accomplished by tying identity to temporary symbols of pseudo-immortality like careers, wealth, and followers.

As Ernest Becker described in The Denial of Death: people build legacies, or subscribe to beliefs that their existence will go beyond the grave.

He also argues that most human behavior, from nationalism to Botox, is a subconscious fear of mortality.

Wrinkles and the loss of fertility signals the approach to decline, irrelevance and loneliness.

In the West, aging has become a symbol of decline. Aging is viewed as a slow fade into irrelevance and invisibility, worsened by social isolation and financial instability in retirement homes.

In comparison to collectivist cultures, elders hold status, knowledge, and respect, and are still seen, heard, and needed.

Aging isn’t bad.

Western society just lacks the structures to value people outside of their output.

So instead, people spend their waking hours performing work that doesn’t feel meaningful in spaces that isolate them from deeper connection or purpose.

This becomes a form of slow death… a creeping disconnection from life: nature, creativity, relationships, spontaneity.

In this framework, people fear not mattering in a system that constantly makes them prove their worth.

Anti-aging, hustle culture, wellness, loneliness, are all symptoms of a culture that denies death because…

Our mortality reminds us that we are disposable.

And a society that is terrified of endings will never stop buying beginnings.

—

Funeral services and cemetery real estate turned death into a business.

Life insurance put a price tag on mortality.

Grief counseling outsources mourning that was once shared by family and community.

THIS is the mortality market:

dying is a problem to fix and a failure to science.

death is put out of sight and moved to hospitals and funeral homes.

death and dying is a paid service.

Are we truly afraid of death or are we just afraid of seeing it?

There is so much anxiety around death even though our ancestors and other cultures already had the cure: proximity.

Bringing Death Back to Daily Life

In Mexico, Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) is a celebration that honors ancestors and embraces death as part of life’s cycle. Families prepare home altars (ofrendas) with candles, flowers, and sugar skulls and children visit cemeteries to picnic on graves.

In Madagascar, Famadihana is a “turning of the bones” ceremony. Families dig up their ancestors’ corpses, re-wrap the skeletons in fresh wraps, and dance with them to live music. It is a ceremony that brings the family together and helps the deceased join the spirit world.

“The dead like music. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t stay so long.”

- Malagasy participant in Famadihana, Ancient Origins' article.

In Tibet, their Buddhist practice opts for a sky burial. The body is taken to a mountaintop and left for vultures. The corpse is viewed as an empty vessel whose spirit has departed. The body return to nature, reinforcing that life and death are a continuous loop.

“We give the body back to the birds. What else would we do? It was never ours to keep.”

- Tibetan practitioner, Atlas Obscura's exploration of sky burial practices.

In impoverished communities where death is visible and constant (war zones and disaster-prone regions), death is not always marked as horror. Sometimes it’s marked as acceptance.

How Modern Funerals Should Be

Good news! The West’s extreme segregation of death isn’t universal or inevitable. The Americans who planted gardens among graves in the 1800s were right to mix life with mourning.

To bridge the gap with death and grief, modern rituals should abandon sanitized funeral norms. This means loved ones lowering the coffin, shoveling the dirt, and grieving together for extended periods.

“They told me not to cry loudly. But the land must know he is gone.”

- Igbo widow, a study on widowhood practices among the Igbo of Eastern Nigeria.

In the West, hope is returning. Online memorials, cemetery tours, public grieving events, death cafés and green burials suggest people are feeling disconnected.

With a loneliness epidemic on the rise, the isolation of mortality leaves many lonely and ill-prepared.

So we must remind ourselves that the grief of the living gains meaning only when we stay close to the reality of death.

“Death is not behind you or in front of you. It walks beside you. You should say hello.”

- Thai monk

—

To Stephen.

Thank you for living through us when you no longer couldn’t.

—

I lived just a few blocks from the city cemetery and the Catholic cemetery. I had relatives in each. As a child, I would pack a bologna sandwich, a bag of chips and some Kool-aid and ride my bike to one of the cemeteries for a picnic. It was always shady, cool and quiet, perfect for a lonely girl to ride her bike and talk to her grandparents she never met. I raised my kids that cemeteries aren’t scary places. It’s where I taught all of them to drive.

I'm so inspired by your project, thank you for sharing this! I wanted to plug this book "On Death and Dying" by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. She is credited with organizing the five stages of grief but the book that introduces it hold so much more value in the timeless insights it offers about Western relationships with death and even alludes to how technology mediates our fear of death.

Here is a quote from the first chapter I found relevant to our current state of AI affairs:

"...Is our concentration on equipment, on blood pressure, our desperate attempt to deny the impending death which is so frightening and discomforting to us that we displace all our knowledge onto machines, since they are less close to us than the suffering face of another human being which would remind us once more of our lack of omnipotence, our own limits and failures, and last but not least perhaps our own mortality?”